New Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab: far-reaching implications of a controversial approval

Positive news from clinical Alzheimer’s research is rare. In hardly any other indication do pharmaceutical companies have to accept as many setbacks as here. To date, pharmacological approaches to treating Alzheimer’s have been almost uniformly unsuccessful, with more than 400 failed clinical trials. Since 2002, there has been no new approval in the field of neurodegenerative diseases.

That changed on June 7, 2021, when the drug Aducanumab, from U.S. biotech Biogen (and its Japanese research partner Eisai), was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. The drug, which is administered intravenously to patients, will be available in the U.S. under the trade mark Aduhelm.

Aduhelm works on the basis of passive immunization. It is a monoclonal antibody that targets amyloid-ß, a protein characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. These amyloid-ß proteins make up the deposits in the brain, known as plaques, which are associated with the destruction of neurones. Aduhelm’s mechanism of action is based on promoting the breakdown of β-amyloid, thereby reducing the harmful plaques.

Problem 1: Controversial approval of aducanumab

The approval of Aduhelm was preceded by a highly controversial debate. The antibody was tested in two phase III trials (Emerge and Engage trials) involving approximately 3285 subjects who were around 70 years of age and had MCI (Mild Cognitive Decline) or Alzheimer’s disease. The trials were stopped early in March 2019 based on an interim analysis using data obtained from approximately 1,700 subjects, as aducanumab did not appear to show benefit.

Then, in October, there was a turnaround: Biogen said that additional data had been analyzed, now totaling about 3,200 subjects. This new analysis showed that there might be a positive effect in the Emerge trial after all, where subjects receiving aducanumab at the highest dose deteriorated mentally at a slightly lower rate than the placebo group: cognition in the high-dose Aduhelm subjects declined 22% less than in the placebo group after 78 weeks. Under the lower dose, the deterioration was 15%, but this effect was not statistically significant.

Thus, in terms of efficacy against cognitive decline, the results were still inconclusive: while the Emerge study suggested that the drug slightly slowed cognitive decline at the higher dose, no positive effect was seen in the Engage study.

Despite this conflicting data, Biogen filed for approval of Aduhelm in October 2020 in consultation with the Food and Drug Administration. The agency approved the application on an expedited basis in June 2021, even though there was a negative recommendation from its external advisory panel the previous November. Ten out of eleven members of this FDA scientific advisory panel – as well as some dementia experts – had opposed approval because, in their view, the evidence of benefit was too weak in relation to the risks.

Problem 2: Reduction of amyloid load, but no patient benefit.

Both critics and supporters of the approval agree on the point that the antibody Aduhelm significantly reduces cerebral amyloid-ß levels. Unfortunately, this has overlooked the fact that the approach being taken with Aduhelm is based on a misconception: In the past, it was believed that Alzheimer’s disease was caused by the accumulation of amyloid-ß in the brain, and that removing the amyloid would eliminate the underlying cause of Alzheimer’s disease. However, this turned out to be false, and it is now known that amyloid-ß is part of the innate immune system response and has many protective functions, including protection against oxidative stress and its antimicrobial effect. Thus, a reduction in amyloid concentration would in no way mean that the disease process could be slowed, stopped, or even reversed. On the contrary, the brain would rather be deprived of a protective function by the antibodies. Consequently, while these drugs were promoted as “disease-reducing agents,” they turned out to be only “amyloid-reducing agents”: the amyloid is successfully reduced, but the Alzheimer’s disease is not improved; on the contrary, the dementia symptoms remain and progress.

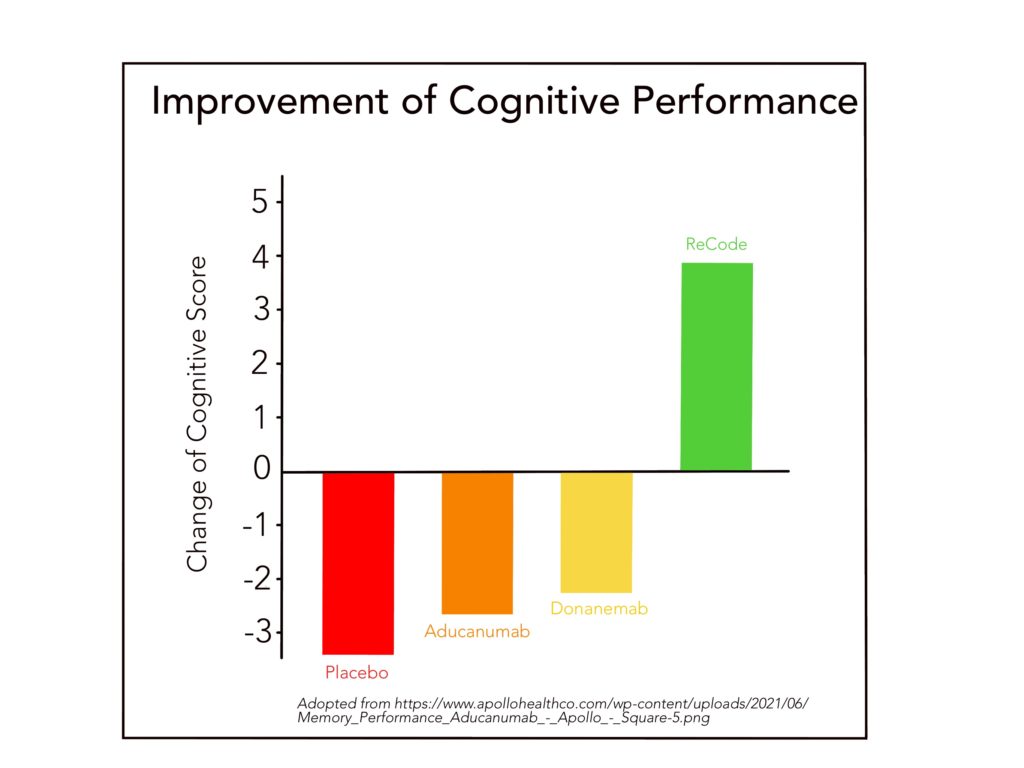

Recently, there have already been some setbacks in antibody therapy for Alzheimer’s: most recently, the manufacturers Roche and AC had stopped the Immune 2 trials with the antibody Crenezumab after an interim analysis of the CREAD 1 and CREAD 2 trials had provided no evidence of slowing cognitive decline. Before that, Eli Lilly & Co had a disappointing setback with Solanezumab in the EXPEDITION trial, but had another antibody called Donanemab currently in regulatory approval. This also showed a significant reduction in amyloid plaques in the Phase II TRAILBLAZER-ALZ trial, but, unsurprisingly, it also failed to halt or cure the disease. Only the progression of cognitive decline could be slowed by about a third.

The study data of the antibody monotherapies are particularly disappointing when compared with the recently published clinical study of the multimodal ReCode concept according to Dr. Dale Bredesen (see figure). This therapy pursues 36 potential targets causally related to Alzheimer’s disease. The clinical study has exemplarily proven that with ReCode, through lifestyle changes, it is possible to stop or reverse the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, especially in its early stages.

Problem 3: Reduction of amyloid load with fatal side effects

In fact, removal of amyloid with Aduhelm in the study resulted in brain swelling, brain hemorrhage, or other unpleasant side effects in about 35% of patients. These potentially life-threatening side effects increased at higher doses and decreased when dosing was discontinued. Of the affected patients, approximately 50% carried the ApoE4 gene. This is precisely the group of patients at increased risk for Alzheimer’s disease and therefore in particular need of an effective therapy. But the one thing the drug does not do is improve cognitive abilities – the only requirement for effective Alzheimer’s therapy!

Problem 4: Gigantic therapy costs

In the American journal The Atlantic, two law professors discuss the economic impact of approving Aduhelm and conclude that the drug’s gigantic cost could force U.S. states to cut other budgets, such as education. It is estimated that approval of the drug could trigger hundreds of billions of dollars in new government spending. No wonder, since the price of the drug will average $56,000 per year per patient. And that figure doesn’t include the additional diagnostic imaging needed to further diagnose or monitor for serious side effects. That’s a quite enormous costs, and all for a drug with a high potential for side effects, whose therapeutic efficacy is also questionable, which was rejected by the expert advisory panel, and whose approval resulted in three resignations from the advisory panel itself. Sadly, this is a classic example of how far the goals of health care and the goals of health care economics diverge, and in this case, economics has prevailed over health.

Conclusion:

In June 2021, a new drug aducanumab (brand name: Aduhelm) from the U.S. company Biogen was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) – the first new drug approval for patients with the neurodegenerative disease Alzheimer’s since almost two decades. The agency granted approval despite a negative recommendation from its external advisory panel and inhomogeneous trial data. Aducanumab is an antibody that specifically targets and has been shown to reduce Alzheimer’s-specific amyloid-ß deposits in the brain. However, it does not attenuate Alzheimer’s disease; on the contrary, dementia symptoms remain and progress. In addition, brain edema and hemorrhage occur in about 35% (!) of patients, and the costs are quite immense, averaging $56,000 per year per patient. Economic experts are already predicting the financial collapse of the US healthcare system.

All this seems almost ironic against the background of the multimodal, lifestyle-oriented therapy concept according to Dr. Dale Bredesen, since with this a demonstrably effective, side-effect-free and significantly less cost-intensive therapy option for Alzheimer’s is available. But fortunately, with this knowledge, you have the choice to opt for the right therapy for your mental health!

Referenzen:

- LH Kuller, OL Lopez (2021) ENGAGE and EMERGE: Truth and consequences? Alzheimers Dement, Apr;17(4):692-695. doi: 10.1002/alz.12286

- K Servick (2019) Doubts persist for claimed Alzheimer’s drug. Science 366 (6471): 1298. doi: 10.1126/science.366.6471.1298

- S. Makin (2018) The amyloid hypothesis on trial, Nature 559: S 4–S 7. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05719-4

- MA Mintun, AC Lo, CD Evans, Ph.D., AM Wessels, et al. Donanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease (2021). N Engl J Med; 384:1691-1704. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2100708

- Sevigny J, Chiao P, Bussière T, Weinreb PH, Williams L, Maier M, et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2016 01;537(7618):50–70.

- https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2021/06/aduhelm-drug-alzheimers-cost-medicare/619169/

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02484547

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02477800

- https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03367403